https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4476167/#supplemental-informationtitle (2015)

Cau et al

Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses that incorporate sufficient character data are able to differentiate the members of such paravian lineages as Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae and Avialae, as demonstrated by our present study. Nevertheless, reinterpretation of Balaur as a flightless avialan reinforces the point that at least some Mesozoic paravian taxa, highly similar in general form and appearance to dromaeosaurids, may indeed be the enlarged, terrestrialised descendants of smaller, flighted ancestors, and that the evolutionary transition involved may have required relatively little in the way of morphological or trophic transformation.

Fossil

evidence for changes in dinosaurs near the lineage leading to birds and the

origin of flight has been sparse. A dinosaur from Mongolia [Mahakala] represents the basal divergence within Dromaeosauridae. The taxon's small body

size and phylogenetic position imply that extreme

miniaturization was ancestral for Paraves (the clade

including Avialae, Troodontidae, and Dromaeosauridae), phylogenetically earlier

than where flight evolution is strongly inferred. In contrast to the sustained

small body sizes among avialans throughout the Cretaceous Period, the two

dinosaurian lineages most closely related to birds, dromaeosaurids and

troodontids, underwent four independent events of gigantism, and in some

lineages size increased by nearly three orders of

magnitude.

So there is evidence of secondarily flightless paravians.

Let us now tie this with the issue of the

statistically poorly supported core nodes. (See earlier posts).

Let's look at Pennaraptora. Pennaraptora is particularly poorly supported. Consequently Oviraptors may not be related to Paraves as sister taxa as commonly presented. Instead,

Oviraptorids (that are dated 10's of millions of years later than basal Paraves) may well be secondarily flightless members of Paraves. And in fact that idea has been proposed over the years.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caudipteryx#Implications

Halszka Osmólska et al. (2004) ran a cladistic analysis that came to a different conclusion. They found that the most birdlike features of oviraptorids actually place the whole clade within Aves itself, meaning that Caudipteryx is both an oviraptorid and a bird. In their analysis, birds evolved from more primitive theropods, and one lineage of birds became flightless, re-evolved some primitive features, and gave rise to the oviraptorids. This analysis was persuasive enough to be included in paleontological textbooks like Benton's Vertebrate Paleontology (2005).[11] The view that Caudipteryx was secondarily flightless is also preferred by Gregory S. Paul,[12] Lü et al.,[13] and Maryańska et al.[14]

The evidence all points to Oviraptorids being secondarily flightless members of derived Paraves. And of course, a few established researchers had already come to that conclusion.

The same logic applies to Ornithomimosaurs (as being secondarily flightless members of derived Paraves).

http://www.bio.fsu.edu/James/Ornithological%20Monographs%202009.pdf

Paul (2002) has argued that

the reason some maniraptoran taxa possess so

many derived avian apomorphies is that they are,

in fact, secondarily flightless birds that are more

derived than basal avian taxa like Archaeopteryx.

Although Paul (2002) retained a theropod ancestry

for birds, support for his hypothesis would

clearly complicate the consensus BMT view. A

few cladistic analyses have retrieved Alvarezsauridae

(e.g., Perle et al. 1993, 1994; Chiappe

et al. 1998) and Oviraptorosauria (Lü et al. 2002,

Marya´nska et al. 2002) as birds more derived

than Archaeopteryx, and other noncladistic studies

have proposed avian status for various oviraptorosaur

(Elzanowski 1999, Lü et al. 2005) and

dromaeosaur taxa (Czerkas et al. 2002, Burnham

2007). These studies have provided support for

elements of Paul’s (2002) hypothesis.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oviraptorosauria#Relationship_to_birds

Oviraptorosaurs, like deinonychosaurs, are so bird-like that several scientists consider them to be true birds, more advanced than Archaeopteryx. Gregory S. Paul has written extensively on this possibility, and Teresa Maryańska and colleagues published a technical paper detailing this idea in 2002.[5][16][17]Michael Benton, in his widely respected text Vertebrate Paleontology, also included oviraptorosaurs as an order within the class Aves.[18] However, a number of researchers have disagreed with this classification, retaining oviraptorosaurs as non-avialan maniraptorans slightly more primitive than the deinonychosaurs.[19]

http://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app47/app47-097.pdf

Avialan status for Oviraptorosauria

TERESA MARYAŃSKA, HALSZKA OSMÓLSKA, and MIECZYSŁAW WOLSAN

This analysis places Oviraptorosauria within Avialae, in a sister−group

relationship with Confuciusornis. Oviraptorosaurs are hypothesized to be secondarily flightless.

The status of oviraptorosaurs as secondarily flightless

birds, more advanced than is Archaeopteryx, has already been

suggested (Paul 1988; Olshevsky 1991; Elżanowski 1999; Lü

2000)

http://theropoddatabase.blogspot.ca/2016/04/database-update-plus-predatory.html

Paul's phylogeny from his influential book.

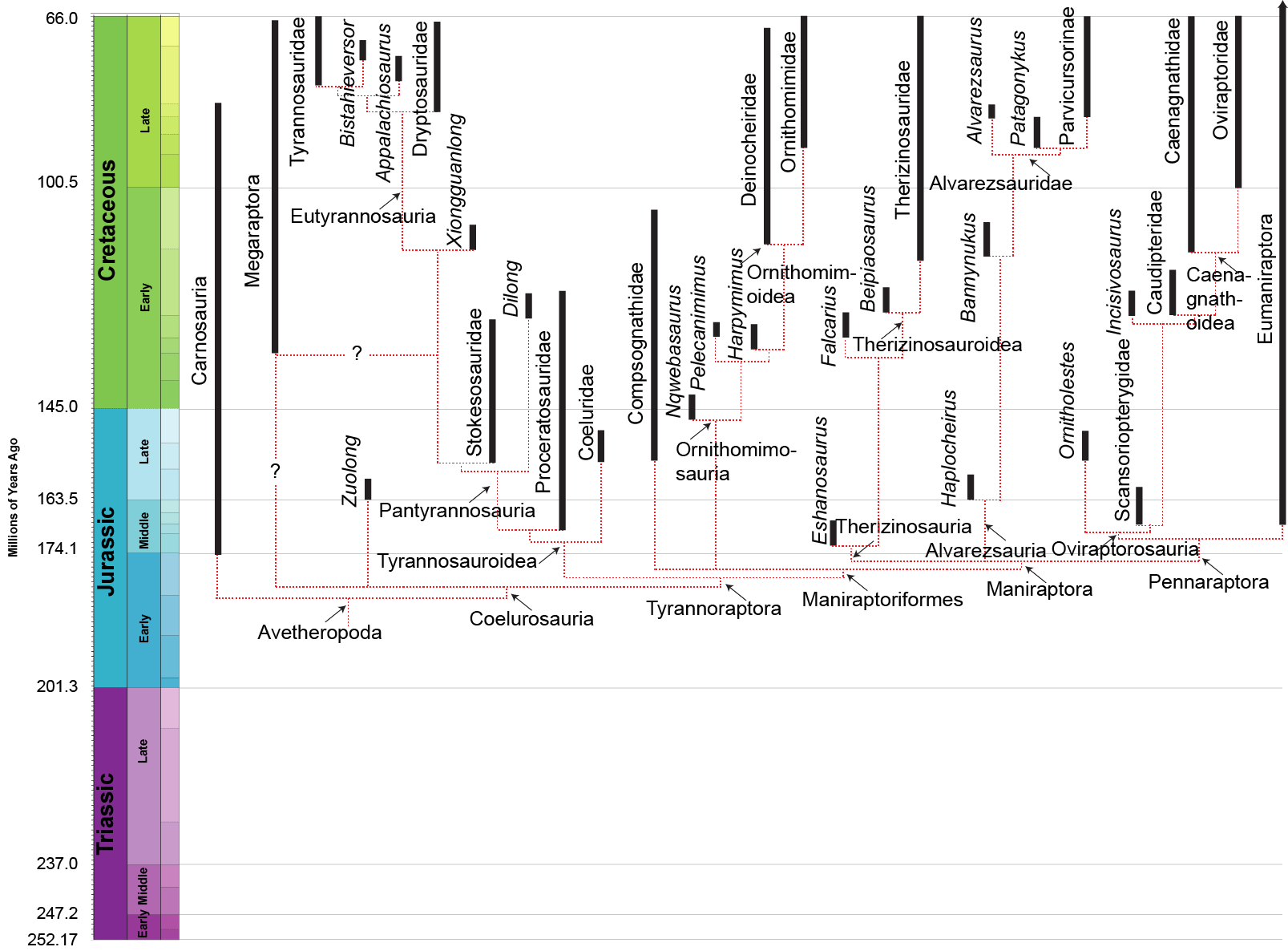

You can see the saltation from Tyrannoraptora to Paraves.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter_Makovicky/publication/274270291_A_Review_of_Dromaeosaurid_Systematics_and_Paravian_Phylogeny/links/576d7b6708ae621947424576.pdf

A REVIEW OF DROMAEOSAURID SYSTEMATICS

AND PARAVIAN PHYLOGENY

ALAN H. TURNER et al

Constraining

Epidexipteryx as a basal oviraptorosaur

requires only one additional step in our

dataset (fig. 75)

The great similarity that exists among basal paravians, basal oviraptorosaurs, and Epidexipteryx

https://bio.unc.edu/files/2011/04/FeducciaCzerkas2015.pdf (2015)

Testing the neoflightless hypothesis:

propatagium reveals flying

ancestry of oviraptorosaurs

Alan Feduccia1 • Stephen A. Czerkas2

The presence of numerous flight features reveal that Caudipteryx, like the extant flightless ratites, originated from volant ancestors (de Beer 1956; Feduccia 2012, 2013), most likely via the evolutionary process of heterochrony, specifically paedomorphosis (arrested development), by which the adult retains the morphology of a younger stage of development (Livesey 1995).

(O'Connor and Sullivan 2014)

Reinterpretation of the Early Cretaceous maniraptoran

(Dinosauria: Theropoda) Zhongornis haoae as a

scansoriopterygid-like non-avian, and morphological

resemblances between scansoriopterygids and basal

oviraptorosaurs The condition present in

Zhongornis resembles that seen in scansoriopterygids (Epidendrosaurus, Epidexipteryx) and

basal oviraptorosaurs (Caudipteryx), which also have proportionately short tails compared to

basal paravians

https://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjU_ujD5crTAhWa3oMKHUKrD4AQFggpMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fagro.icm.edu.pl%2Fagro%2Felement%2Fbwmeta1.element.agro-article-f0207f80-7285-42b0-a431-2ef5fa0d0c1b%2Fc%2Fapp50-101.pdf&usg=AFQjCNFNsUhAlBSjTbQ56gadn7tXHtdmuw&sig2=3boXRPl-fvXrXf6GDDZX6w

Dyke G J, Norell M A, 2005. Caudipteryx as a non-avialan theropod rather than a flightless bird. Acta Palaeont Pol, 50(1):

101–116

There is no reason—phylogenetic, morphometric or otherwise—to conclude that Caudipteryx is anything other than a small non−avialan theropod dinosaur.

NOTE:

"Non-avian theropod" could still be a member of Paraves.

Oviraptors were either secondarily flightless avialae or secondarily flightless non-avialae paraves.

They descended from flying ancestors. They are not transitional between dinosaurs and paraves.

Gregory Paul

https://books.google.ca/books?id=OUwXzD3iihAC&pg=PA252&lpg=PA252&dq=Oviraptorosauria+exaptation&source=bl&ots=H2Af0-ZfpR&sig=Z4NANr-dJbukOeiT_jnTL9Jya3g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj9-oGNwNbTAhUL2IMKHed9BngQ6AEIKTAB#v=onepage&q=Oviraptorosauria%20exaptation&f=false

http://evolutionwiki.org/wiki/Velociraptor_a_Mesozoic_kiwi%3F_A_look_at_the_neoflightless_hypothesis

The past two decades have witnessed the collapse of every single classical autapomorphy (or “holodiagnostic” to use Charig’s term) of Aves, from furculae, to feathers. Accordingly, distinguishing a par-avian theropod from a bona fide bird, is increasingly a matter of subjectivity. Add into this mess the argument that taxa traditionally classified as lying outside Aves are in fact neoflightless forms closer to Neornithes than is Archaeopteryx, and you have enough to drive the prospective student of avian phylogenetics to despair.

http://www.ivpp.cas.cn/qt/papers/201403/P020140314389417822583.pdf

In order to test previous suggestions that oviraptorosaurs might be basal avialans, we ran two

additional analyses. The first of these analyses was constrained to produce a monophyletic

group comprising all oviraptorosaurian and non-archaeopterygid avialan species, whereas the

second was constrained to produce a monophyletic group comprising all oviraptorosaurian

and avialan including archaeopterygid species. The first analysis resulted in 1096 most

parsimonious trees, each having a length of 1410 steps. Figure S10 shows the strict consensus

of the 1096 trees. The second analysis resulted in 216 most parsimonious trees, each having a

length of 1413 steps. Figure S11 shows the strict consensus of the 216 trees. These analyses

indicate that the hypotheses that recover an Oviraptorosauria-Avialae clade are considerably

less parsimonious than the hypothesis shown in Figure 6. However, one reason that the

Oviraptorosauria-Avialae hypotheses are worse supported by our dataset might be the large

amount of missing data from the palates and braincases of the basal oviraptorosaurs and basal

avialans, regions that represent important sources for oviraptorosaurian synapomorphies.

In oviraptorosaurs and basal avialans the

supraacetabular crest is absent.

https://www.geol.umd.edu/~tholtz/G104/lectures/104coelur.html

The remaining maniraptorans form the clade Pennaraptora ("feathered raptors"). These comprise the oviraptorosaurs, the scansoriopterygids, and the eumaniraptorans. These groups are united by several important characteristics:

- Another increase of brain size

- Laterally directed shoulder joint

- Honest-to-goodness pennaceous feathers on at least the arms and tail (their presence on arms at least are documented further down the tree, at least shared with ornithomimosaurs)

- Brooding on nests of eggs (may have been present in more basal coelurosaurs)

http://www.dinosaur-museum.org/featheredinosaurs/Are_Birds_Really_Dinosaurs.pdf

With the benefit of hindsight it is easy to see that if fossils of the small flying dromaeosaurs from China had only been discovered before the larger flightless dromaeosaurs like Deinonychus or Velociraptor were found, the interpretations of the past three decades on how birds are related to dinosaurs would have been significantly different. If it had already been established that dromaeosaurs were birds that could fly, then the most logical interpretation of larger flightless dromaeosaurs found afterwards would have to be that they represented birds, basically like the prehistoric equivalent of an Ostrich, which had lost their ability to fly.