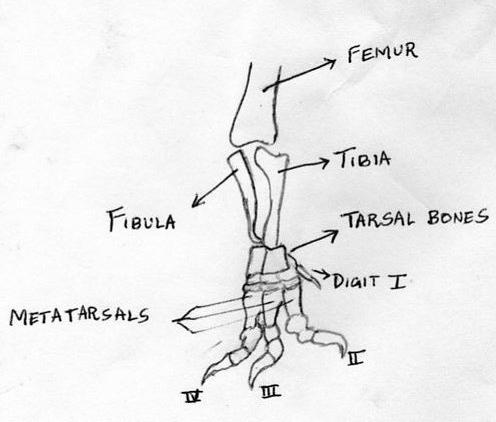

Zhang et al. also noted that the foot of Scansoriopteryx is unique among non-avian theropods; while Scansoriopteryx does not preserve a reversed hallux (the backward-facing toe seen in modern perching birds), its foot was very similar in construction to primitive perching birds like Cathayornis and Longipteryx. These adaptations for grasping ability in all four limbs, the authors argued, makes it likely that Scansoriopteryx spent a significant amount of time living in trees.[1]

Scansoriopteryx has a better-preserved foot than the type of Epidendrosaurus, and the authors interpreted the hallux as reversed, the condition of a backward-pointing toe being widespread among modern tree-dwelling birds.

Later taxa did have a hyperextended second toe.

Archaeopteryx second toe held off the ground in a hyperextended position.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeopteryx

Despite its small size, broad wings, and inferred ability to fly or glide,Archaeopteryx has more in common with other small Mesozoic dinosaurs than it does with modern birds. In particular, it shares the following features with the deinonychosaurs (dromaeosaurs and troodontids): jaws with sharp teeth, three fingers with claws, a long bony tail, hyperextensible second toes ("killing claw"), feathers (which also suggest homeothermy), and various skeletal features.[4][5]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraves

Like other theropods, early paravians are bipedal; that is, they walk on their two hind legs. However, whereas most theropods walked with three toes contacting the ground, fossilized footprint tracks confirm that many basal paravians, including dromaeosaurids, troodontids, and some early avialans [eg. Archaeopteryx] held the second toe off the ground in a hyperextended position, with only the third and fourth toes bearing the weight of the animal. This is called functional didactyly.[5] The enlarged second toe bore an unusually large, curved sickle-shaped claw (held off the ground or 'retracted' when walking).

http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/archaeopteryx/challenge.html

The shoulder joint of Archaeopteryx is more similar to the theropod dinosaur Deinonychus, than to modern birds (Jenkins 1993), the shoulder joint of the ostrich is more similar to other birds than to the shoulder joint of Archaeopteryx. The wrist joint of the ostrich is partially fused as in modern birds, whereas the wrist joint of Archaeopteryx is not, as in typical reptiles. The fingers of the ostrich wing are fused together as in modern birds, the fingers of Archaeopteryx are free, as in typical reptiles. Thus, the wing of the ostrich can in no way be described as "even more reptile-like than those of Archaeopteryx."

Pubic bones

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/279/5358/1915

"The pelvic elements of Rahona closely resemble those of Archaeopteryx and Unenlagia (18). The ilium has a long preacetabular process (55% of the ilium length) and a short postacetabular process that is drawn back into a narrow, pointed posterior end. The pubis (90% of the ilium length) is oriented vertically (as in some maniraptorans, Archaeopteryx, and Unenlagia). Distally, the pubis sweeps caudally and expands into a foot; a well-developed hypopubic cup is present (Fig. 4A). A pubic foot is absent in nearly all avians, but is present in theropods, Archaeopteryx, Patagonykus, and enantiornithines (for example, Sinornis and Cathayornis).

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091009090436.htm

The raptor-like Archaeopteryx has long been viewed as the archetypal first bird, but new research reveals that it was actually a lot less "bird-like" than scientists had believed.

Surprisingly, the bones of the juvenile Archaeopteryx were not the highly vascularized, fast-growing type, as in other avian dinosaurs. Instead, Erickson found lizard-like, dense, nearly avascular bone.

http://gimpasaura.blogspot.ca/2015/02/people-snatching-pterosaurs.html

Pterosaurs have slender, weakly muscled feet. While the earlier non-pterodactyloids had 4 long, slender clawed digits that would have been flat on the ground during walking (in a plantigrade posture), the 5th digit was still elongated but did not touch the ground when walking (but was also not reversed as seen in birds). In more derived pterodactyloids, the 5th digit is almost entirely lost. None of these digits are reversed like in birds, and do not show the grasping structure as is typically shown in movies.http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/saurischia/theropoda.html

Other theropod characters include modifications of the hands and feet: three main fingers on the manus (hand); the fourth and fifth digits are reduced; and three main (weight-bearing) toes on the pes (foot); the first and fifth digits are reduced. Most theropods had sharp, recurved teeth useful for eating flesh, and claws were present on the ends of all of the fingers and toes. Note that some of these characters are lost or changed later in theropod evolution, depending on the group in question.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraves

Most theropods walked with three toes contacting the ground, but fossilized footprint tracks confirm that many basal paravians, including dromaeosaurids, troodontids, and some early avialans, held the second toe off the ground in a hyperextended position, with only the third and fourth toes bearing the weight of the animal. This is called functional didactyly.[2] The enlarged second toe bore an unusually large, curved sickle-shaped claw (held off the ground or 'retracted' when walking). This claw was especially large and flattened from side to side in the large-bodied predatory eudromaeosaurs.[11] In these early species, the first toe (hallux) was usually small and angled inward toward the center of the body, but only became fully reversed in more specialized members of the bird lineage.[4]

http://palaeos.com/vertebrates/coelurosauria/paraves.html

Deinonychosauria includes the two groups of coelurosaurs with a switchblade second toe claw, dromaeasaurs and troodontids.

https://finstofeet.com/tag/dinosaurs/

The classic Theropod foot sports three weight-bearing toes – the 2nd, 3rd and 4th digits. The first toe is small and – in many cases – raised such that it does not make contact (or makes limited contact) with the ground during normal locomotion on a hard substrate. It also diverted towards the rear in a number of Theropod groups. The fifth digit is either greatly reduced or altogether absent.

No comments:

Post a Comment